The Right to Vote

The voting process in the United States has never been simple, easy, or without controversy. The U.S. Constitution gave individual states the power to determine who could legally vote. This means that throughout American history, a person’s ability to vote has been impacted by where they lived.

Those in power have at times used factors such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, income, property ownership, and education to deny voting rights to large portions of the population. Federal laws and amendments to the U.S. Constitution have eliminated some voting restrictions and imposed others, and some issues continue to evolve.

Aside from legal barriers, voting is also a matter of who feels inspired and empowered to exercise that right. Voting is one of the most effective ways that citizens can bring about change. National elections may generate the greatest voter turnout, but local and state elections are equally important, since decisions made by local and state lawmakers often directly impact who can vote and how those votes are counted.

The artifacts highlighted here reflect just some of the many factors that have affected citizens’ voting rights.

Affidavit of Unregistered Voter

1862

In the mid-1800s, some states tried to safeguard elections by passing laws that required voters to register in advance. This caused problems for some residents who might not know they needed to register, or when or where to do so. However, an unregistered voter could still cast a ballot if he could find a “householder” (head of a household) to vouch for him by signing an affidavit. This practice may have served to suppress the political voices of less-advantaged people, who might have been less likely to have friends who were householders.

This statement, signed on election day in 1862, says that Gustavus A. Wever failed to appear in advance because “he forgot it.” Householder Joseph Silva, who signed with a mark (suggesting he was unable to write his name), vouched for the identity of Mr. Wever.

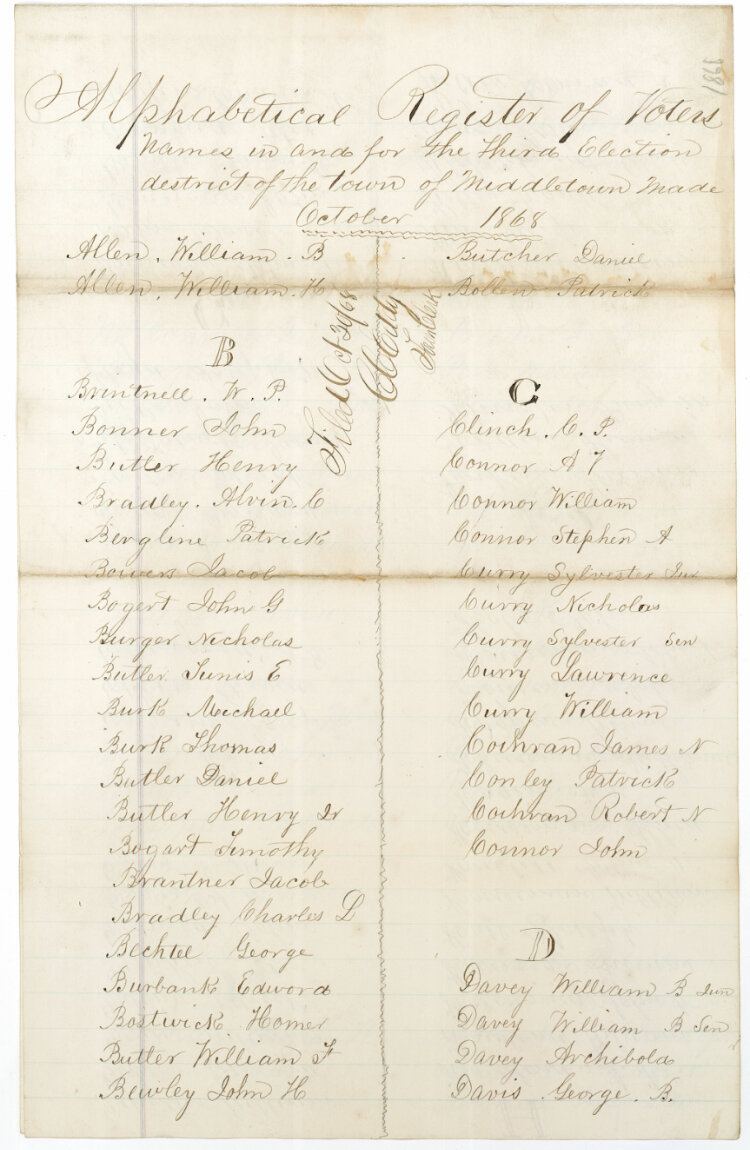

Alphabetical Register of Voters

October 1868

After New York State adopted a new constitution in 1846, laws were passed establishing rules for registering voters. Voters were required to register in person on specific days, which were published in local newspapers. This document lists names of registered voters in the third election district in Middletown, Staten Island, in October 1868, a month before the first presidential election in which formerly enslaved Americans had the right to vote.

Middletown included the village of Stapleton, which was home to both German immigrant and African American communities. The name of George Bechtel, a local brewer who immigrated to Staten Island from Germany, can be found in the left-hand column of this register. It is not currently known whether any of the people listed here were African American.

Statement of Votes Given for Electors of President

November 3, 1868

The year 1868 marked the first U.S. presidential election after the passage of the 14th Amendment, which granted citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including people who had formerly been enslaved. Nationwide, more than 700,000 African American men voted for the first time. This statement of votes records the results of an election held that year in the town of Middletown, Staten Island.

Voters at a general election at that time did not cast their votes directly for President and Vice President of the United States. Instead, they voted for a slate of electors, who would then cast their votes as members of the Electoral College. Examples of ballots for each party are attached to the statement. At the top is the Republican ticket, which includes the name of George William Curtis, a noted Staten Island abolitionist and suffragist. He, along with the other electors on this ticket, would go on to cast his vote for Ulysses S. Grant, who won the national election.

Poll list of Election District No. 1

May 17, 1870

This list records the names of people who voted in a special election held on May 17, 1870, in election district No. 1 in the town of Southfield, Staten Island. This was the first local election in which African American men were guaranteed the right to vote by the 15th Amendment.

This district included the village of Richmond, and among the names on the list are several residents of houses that are now part of Historic Richmond Town, including Stephen Dover Stephens, Sr., of the Stephens-Black House and General Store. Poll lists were used to check that the total number of ballots in the ballot box was the same as the number of voters, and that no others had been added inappropriately.

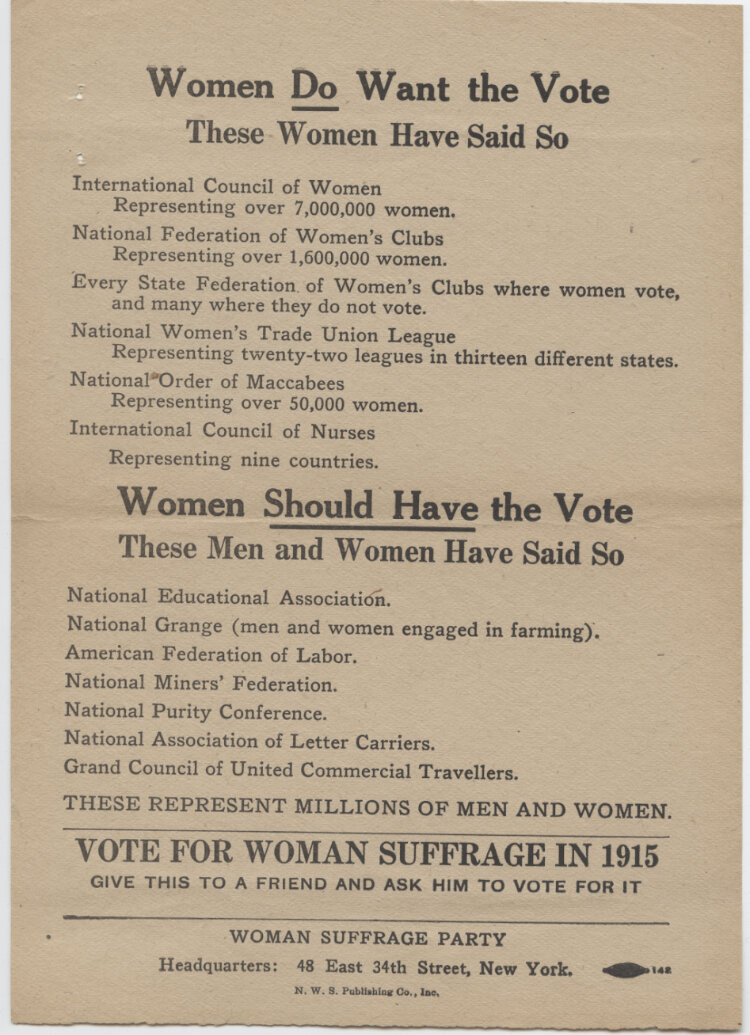

Handbill in Support of Women’s Suffrage

1915

The Woman’s Rights Convention held at Seneca Falls in 1848 is known for launching the women’s suffrage movement, but it took over 70 years for women in the United States to be guaranteed the right to vote. Early on, many supporters of the movement worked for and hoped to win the right to vote for women and African Americans at the same time, and tensions arose when this was found to be politically impossible. As the nation expanded westward, some of the newly-formed states gave women voting rights in their constitutions, while women in older states still lacked those rights.

Suffragists worked to change this by campaigning for new laws in each state allowing women to vote, and for a constitutional amendment that would grant women in the whole country the right to vote. They joined protests, marched in processions, attended mass meetings, and handed out leaflets to encourage men to vote for women’s rights. In 1917, the women of New York State gained the right to vote, and three years later in 1920, the 19th Amendment guaranteed American women in every state the right to vote.

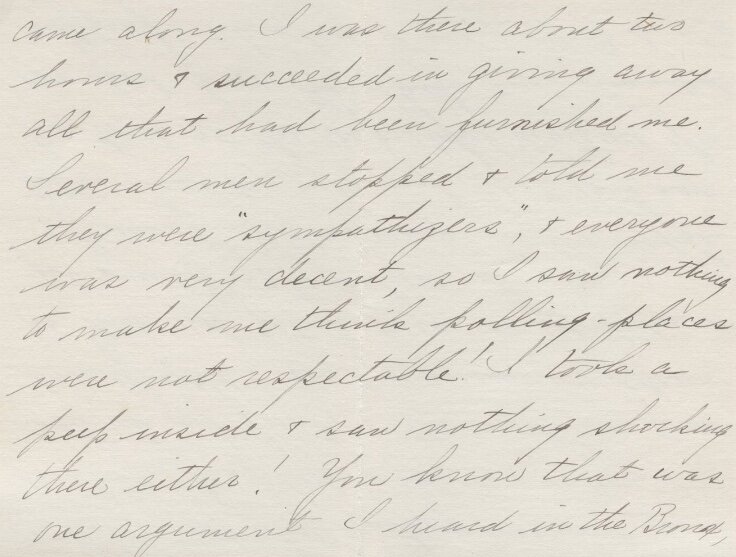

Letter written by Linda French (pages 2 and 3)

Staten Island

November 5, 1914

Linda French, a Staten Island school teacher, was actively involved in the women’s suffrage movement. In this letter to her mother, she describes how she handed out pro-suffrage leaflets at the polls. Her description begins near the bottom of the second page and continues on the third page:

"I went 'electioneering' for the suffragettes Tuesday morning. That is to say, I stood at the respectful distance of 100 feet from the polls and handed suffrage literature to every MAN that came along. I was there about two hours & succeeded in giving away all that had been furnished me. Several men stopped & told me they were 'sympathizers', & everyone was very decent, so I saw nothing to make me think polling-places were not respectable! I took a peep inside & saw nothing shocking there either! You know that was one argument I heard in the Bronx, --that the polling places were so dreadful that it would not be proper for women to go there. But I suppose Stapleton would not be like New York City..."

Richard M. Nixon Campaign Button

1960

It was not until 1971 that the 26th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution lowered the voting age from 21 to 18. This pin is from the 1960 U.S. Presidential campaign, in which Richard M. Nixon, then Vice President, was defeated by John F. Kennedy. Nixon was elected president in 1968 and re-elected in 1972 (after the voting age was lowered). He served until his resignation in 1974.